FROM OUR PRINTED JULY 2022 EDITION

Review — Matti Friedman, WHO BY FIRE: Leonard Cohen in the Sinai

by Len Abram

Boston Broadside Columnist

“Let us now relate the power of this day’s holiness, for it is awesome and frightening … who shall live and who shall die, who by water and who by fire …” For centuries Jews have read this ancient prayer during Yom Kippur, the Day of Atonement, the most solemn day in the Hebrew calendar.

As a community, Jews are told to “afflict their souls.” For 24 hours, Jews refrain from food, drink, bathing, even sex. It’s a denial of the physical self, some say to feel mortal and weak, dehydration the most challenging. The deprivation of the physical aims to lead Jews toward the spiritual, such as atoning for their sins and reaffirming their faith. Yom Kippur also has in it a life review similar to what people at secular New Year’s consider, resolving to do better in the coming year.

On Yom Kippur of October 6, 1973, at synagogues or in their homes, Israelis did not know a war had begun that would decide who would live or who would die, the fire this time from the bullets, rockets, shells, and bombs of attacking Egyptian and Syrian armies. With extensive research and interviews, Matti Friedman, who served in the Israeli army in the 1990s, has written a brief, compelling history of the October war, and the musician who brought comfort to Israelis who waged it.

Nearly a half century ago, Egypt and Syria attacked the IDF, Israel’s armed forces, with disastrous results. Israel had thin lines of defense on the Suez Canal and the Golan Heights, partly from over-confidence following its spectacular victories in the 1967 war. The theory was that the lines would hold long enough for Israel’s reserves of several hundred thousand to be mobilized. Israel’s edge in technology in the air and its tanks on the ground would be enough to dissuade or to destroy.

Early in the war, Arab antiaircraft missiles, anti-tank rockets and artillery from the Soviet Union devastated Israeli defenses, aircraft and tanks. Israeli aircraft had no defense against antiaircraft missiles the size of telephone poles chasing them down. In the Sinai, without aircraft cover, Israeli tanks engaged swarms of Egyptian infantry armed with missiles and rockets. With severe losses, and their technical edge gone, Israeli infantry on the ground had to win the battles.

That meant many casualties, which for a small population was all the more painful. In one scene in Friedman’s book, 11 Israeli army trucks deliver 11 bodies of kibbutz members killed in the fighting. For this secular kibbutz, Yom Kippur has had a deeper meaning since. One unforeseen result of the tragic war was to turn some secular Israelis back to their religion. By the end of October, Israel had regained territory and deterrence. Although a peace settlement took them out of Sinai, Israel was still sovereign over the Golan. The victories seemed like defeats, with over 2500 Israelis dead, and many more wounded.

Friedman’s history of the war focuses on the few gruesome weeks when survival of the army and perhaps the Jewish state itself were in doubt. The country had gone from confidence to despair, a crucial loss in morale. Along with more troops and supplies, the beleaguered soldiers and pilots needed to regain their purpose and faith.

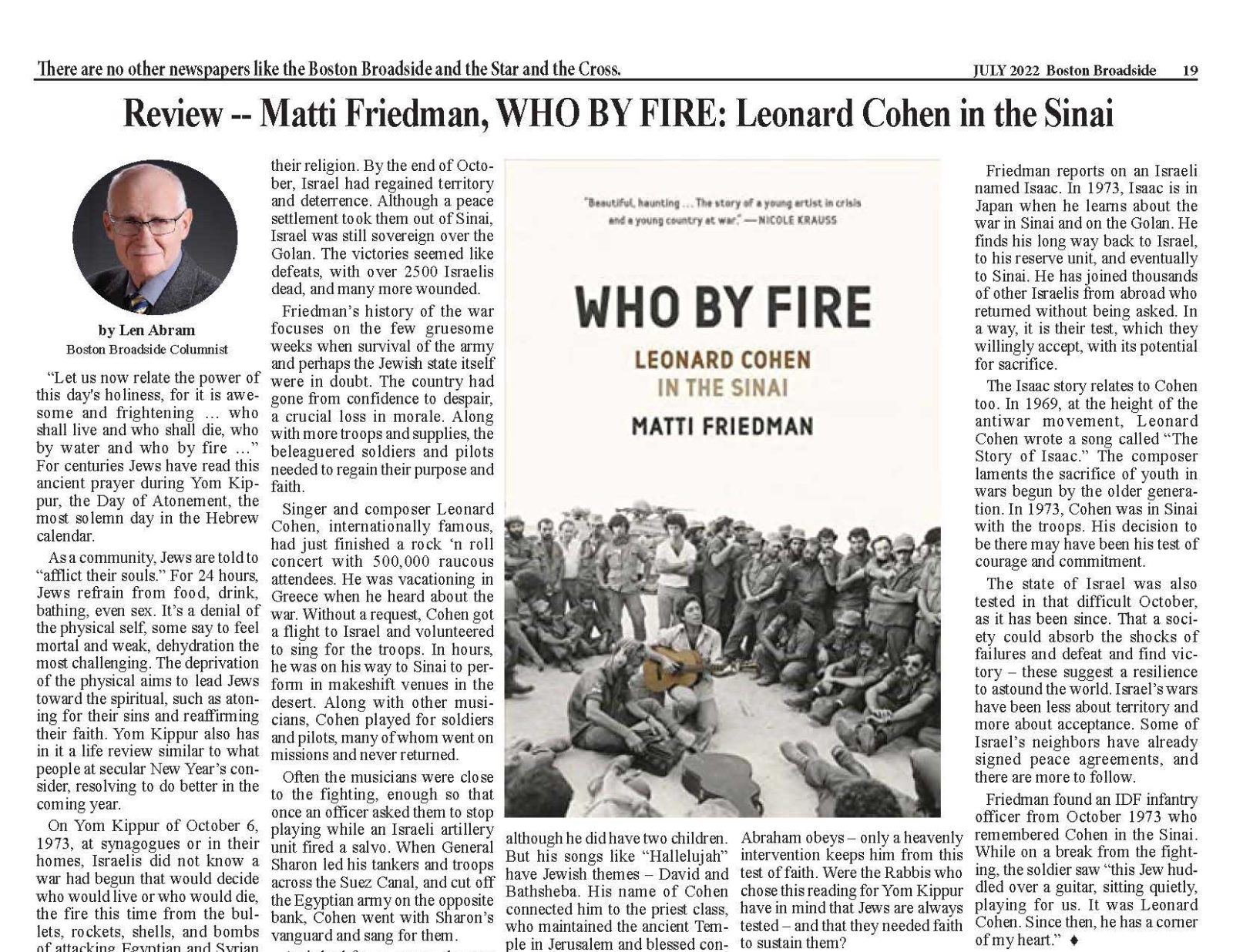

Singer and composer Leonard Cohen, internationally famous, had just finished a rock ‘n roll concert with 500,000 raucous attendees. He was vacationing in Greece when he heard about the war. Without a request, Cohen got a flight to Israel and volunteered to sing for the troops. In hours, he was on his way to Sinai to perform in makeshift venues in the desert. Along with other musicians, Cohen played for soldiers and pilots, many of whom went on missions and never returned.

Often the musicians were close to the fighting, enough so that once an officer asked them to stop playing while an Israeli artillery unit fired a salvo. When General Sharon led his tankers and troops across the Suez Canal, and cut off the Egyptian army on the opposite bank, Cohen went with Sharon’s vanguard and sang for them.

As it had for so many, the war changed Cohen too. In 1973, at nearly 40, Cohen thought his career was over. He had written classics still sung today: “Suzanne,” “Hallelujah,” and “Lover Lover Lover.” But his songs celebrated the 60s culture of sex, drugs, and rock n’ roll. The 60s knew what they were rebelling against, but Friedman suggests that Cohen himself wasn’t sure of what he was for.

Cohen struggled with commitment, to marriage and to his Jewish faith. Cohen never married, although he did have two children. But his songs like “Hallelujah” have Jewish themes – David and Bathsheba. His name of Cohen connected him to the priest class, who maintained the ancient Temple in Jerusalem and blessed congregations since. Cohen moved closer to his Jewish identity in Sinai. Rather than at the end of his career, Cohen wrote and sang for decades more until his death in 2016.

Friedman handles the material of history, theology and character like a novelist. The Yom Kippur service has in it perhaps the most troubling episode in the Torah or Hebrew Bible – the Sacrifice of Isaac. Abraham is told by God to take his only son by his wife Sarah to a mountain top where he will sacrifice the boy on an altar. Abraham obeys – only a heavenly intervention keeps him from this test of faith. Were the Rabbis who chose this reading for Yom Kippur have in mind that Jews are always tested – and that they needed faith to sustain them?

Friedman reports on an Israeli named Isaac. In 1973, Isaac is in Japan when he learns about the war in Sinai and on the Golan. He finds his long way back to Israel, to his reserve unit, and eventually to Sinai. He has joined thousands of other Israelis from abroad who returned without being asked. In a way, it is their test, which they willingly accept, with its potential for sacrifice.

The Isaac story relates to Cohen too. In 1969, at the height of the antiwar movement, Leonard Cohen wrote a song called “The Story of Isaac.” The composer laments the sacrifice of youth in wars begun by the older generation. In 1973, Cohen was in Sinai with the troops. His decision to be there may have been his test of courage and commitment.

The state of Israel was also tested in that difficult October, as it has been since. That a society could absorb the shocks of failures and defeat and find victory – these suggest a resilience to astound the world. Israel’s wars have been less about territory and more about acceptance. Some of Israel’s neighbors have already signed peace agreements, and there are more to follow.

Friedman found an IDF infantry officer from October 1973 who remembered Cohen in the Sinai. While on a break from the fighting, the soldier saw “this Jew huddled over a guitar, sitting quietly, playing for us. It was Leonard Cohen. Since then, he has a corner of my heart.” ♦

Great article!!